Hades in Chains, Shattered Doors in a Sea of Flames and Horrifying Faces of Hell: The Manifold Depiction of the Harrowing of Hell

For as Jonas was three days and three nights in the whale's belly; so shall the Son of man be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth. (Mt 12:40)

With these words, Jesus announces his resurrection for the third time according to the evangelist Matthew. But where was Christ's soul after his crucifixion and in the time leading up to the Easter resurrection? Christian scholars and believers were already asking themselves this question in late antiquity. According to the so-called Gospel of Nicodemus, the spirit of Jesus descended into the underworld the night after his death on the cross, overcame its Christian or mythological masters Satan and Hades and saved the souls of the righteous – forefathers, patriarchs, prophets, martyrs – starting with Adam and Eve.

To the facsimile

In the Early Middle Ages, the belief in this Harrowing of Hell, also known as Christ in Limbo or Christ's Descent into Hell (Latin: Descensus Christi ad inferos) spread in both the Eastern and Western churches, which went hand in hand with the need to visually capture and depict the deeds of the Son of God. Several impressive iconographic solutions emerged, which were artistically varied until the 16th century and are all characterized by gruesome infernal creatures and horrific images of the netherworld.

While Satan and Hades were thus talking together, a mighty voice rang out like thunder: 'Open, you rulers, your gates, open eternal gates! The King of Glory will enter. (EvNic 5,1)

To the facsimile

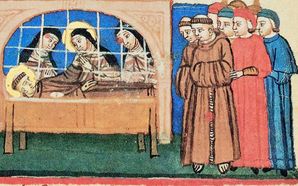

The incomplete legend of Christ's Descent into Hell is primarily based on the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus. Apocrypha are religious writings that were not included in the biblical canon. Nicodemus is described in the Gospel of John as a Pharisee who stands up for Jesus before the authorities and also attends the entombment. He was therefore a contemporary witness of Jesus and is said to have been the original author of this apocryphal gospel, which complements the extremely vague hints in the Bible regarding the whereabouts of Christ's soul between the crucifixion and resurrection. Thus the First Letter of Peter 3:18-19 simply states:

"For Christ also hath once suffered for sins, the just for the unjust, that he might bring us to God, being put to death in the flesh, but quickened by the Spirit: By which also he went and preached unto the spirits in prison."

Experience more

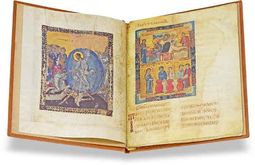

Crossed Doors and Hades in Chains: The Iconography of the Harrowing of Hell in Byzantine Art

To the facsimile

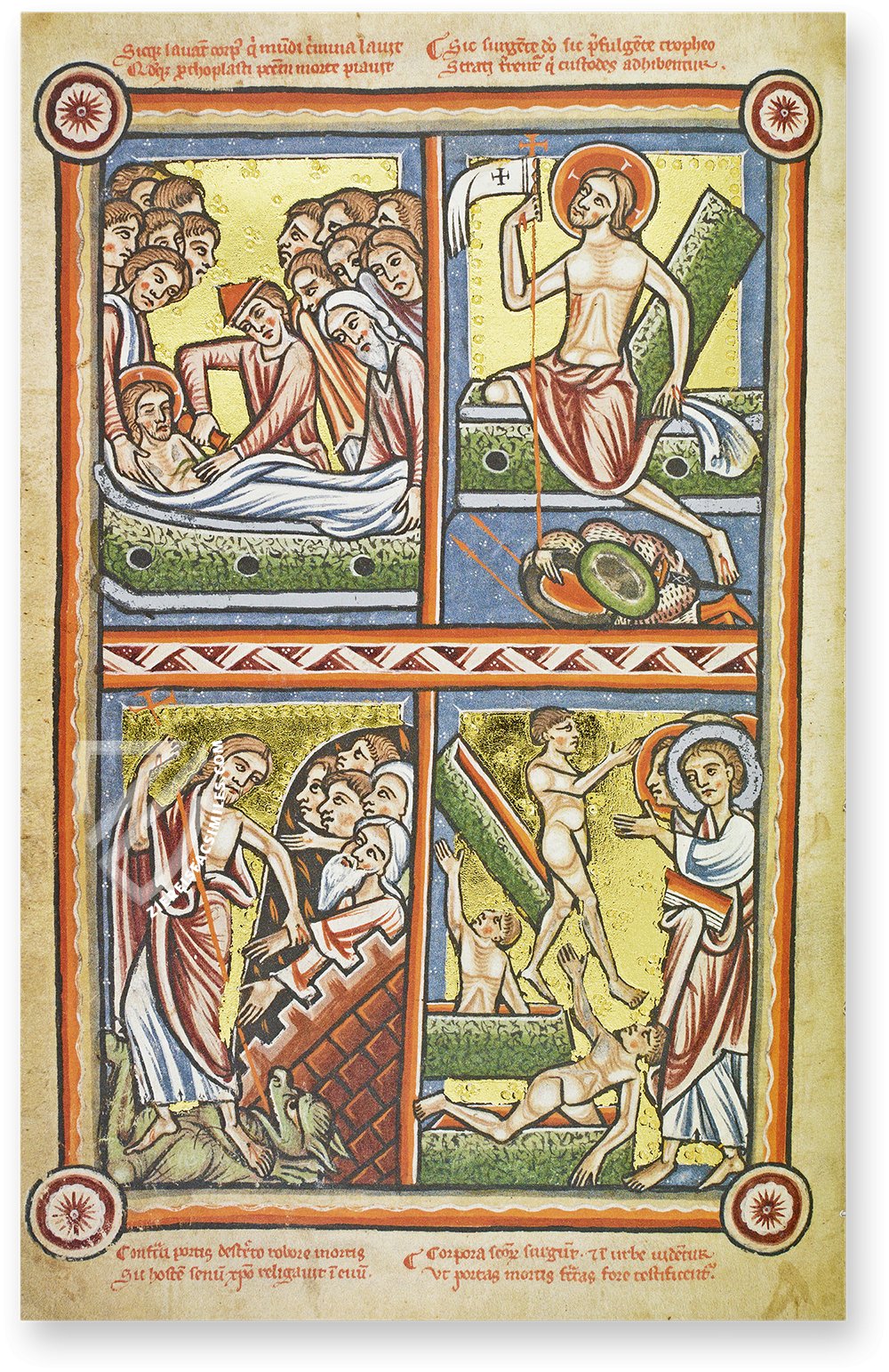

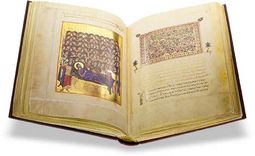

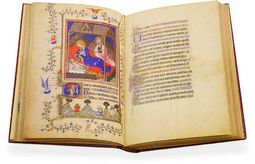

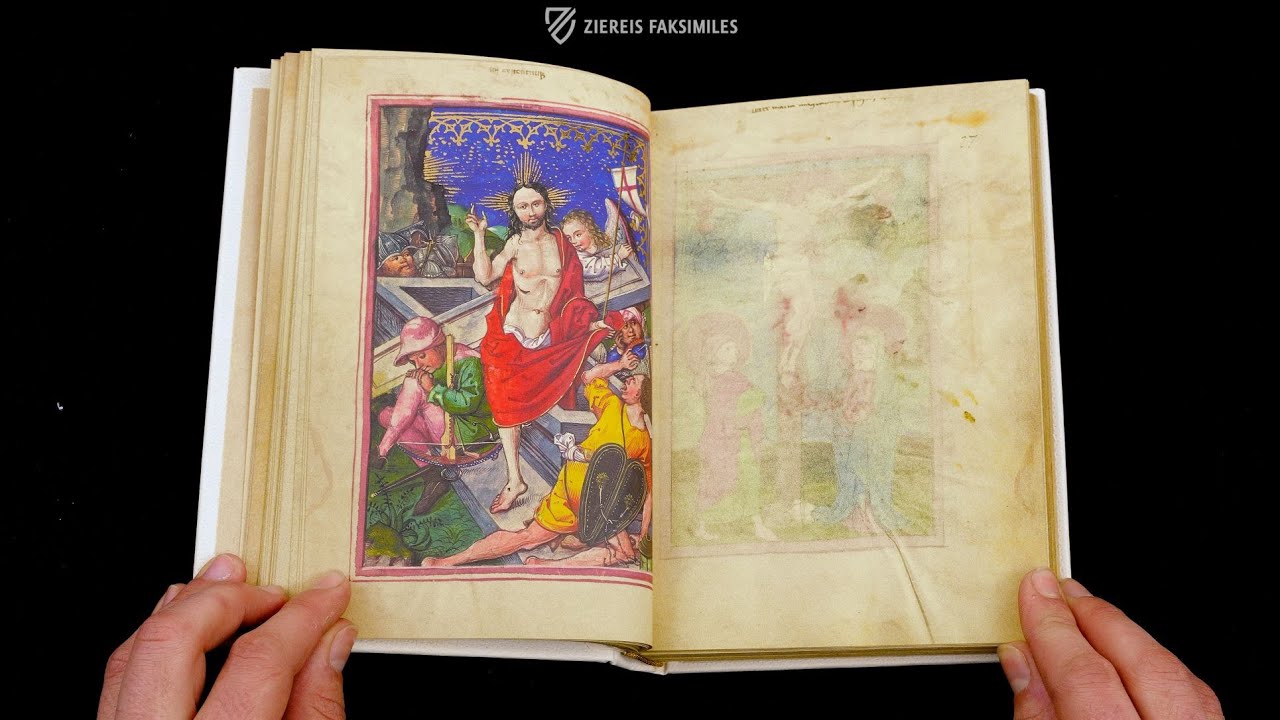

Since the Early Middle Ages, Christ's Descent into the Underworld has had a significant meaning for the salvific history. In the Byzantine Eastern Church, the Resurrection was associated with the Harrowing of Hell and the salvation of the righteous. The result was the Icon of the Anastasis, which is still a central image in Orthodox art today. It is the Easter and Resurrection image par excellence, as it bears dual witness to the redemptive work of Christ, who not only conquers his own death, but also redeems humanity from it – for the first time during his Descent into Hell. This fundamental pictorial solution probably originated in the Syrian-Palestinian region and was then spread throughout the Byzantine Empire.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

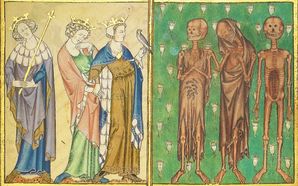

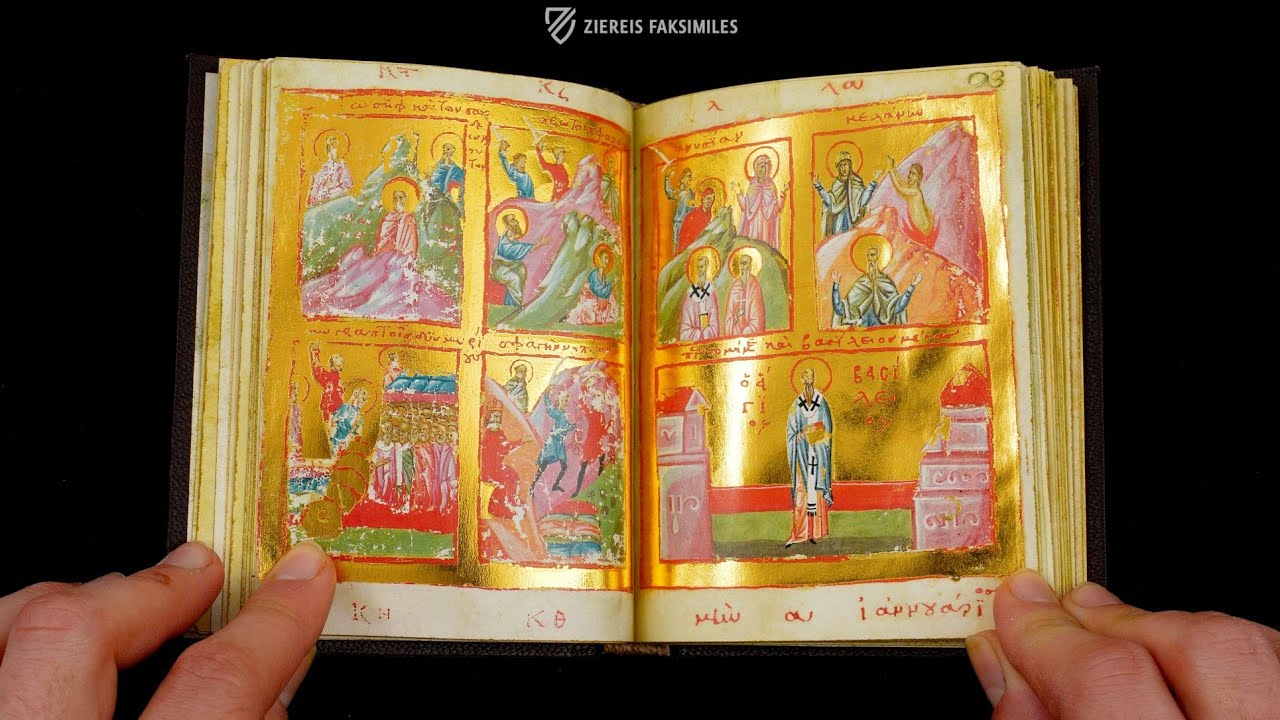

In medieval Byzantine art, the iconography of the Harrowing of Hell is characterized above all by the fact that Christ, bending down to his ancestors Adam and Eve, stands on the defeated Hades, who usually lies shackled on the ground. Christ often appears in a large aureole and holds a cross staff as an attribute to symbolize his triumph. Usually, the shattered doors of hell are also depicted at his feet, often in a crossed arrangement as in the miniature of the Marian Homilies. Christ first grabs Adam's hand, followed by Eve and the other saints, all of whom he frees from the gloomy and only vaguely depicted netherworld or from sarcophagi.

To the facsimile

And at the same time the iron gates were broken down and the iron crossbars were broken, and the bound dead were all loosed from their bonds. (EvNic 5,3)

Some Byzantine depictions also present the pictorial theme without Hades, such as in the Oxford Menologion. Instead, it shows Jesus standing on the shattered and crossed gates of hell, which are often highlighted in this variation – here in bright gold.

To the facsimile

Experience more

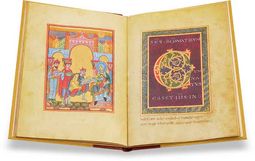

The Iconography of the Descent into Hell in the West: Christ Snatches Adam from the Flames of Hell

To the facsimile

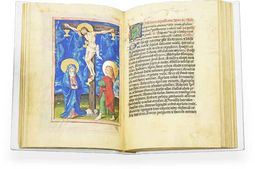

In Western European Christian art, the association of hell with heat, fire and flames was established early on. It is therefore not surprising that in most Western depictions of Christ in Limbo, blazing flames flicker out of the underworld.

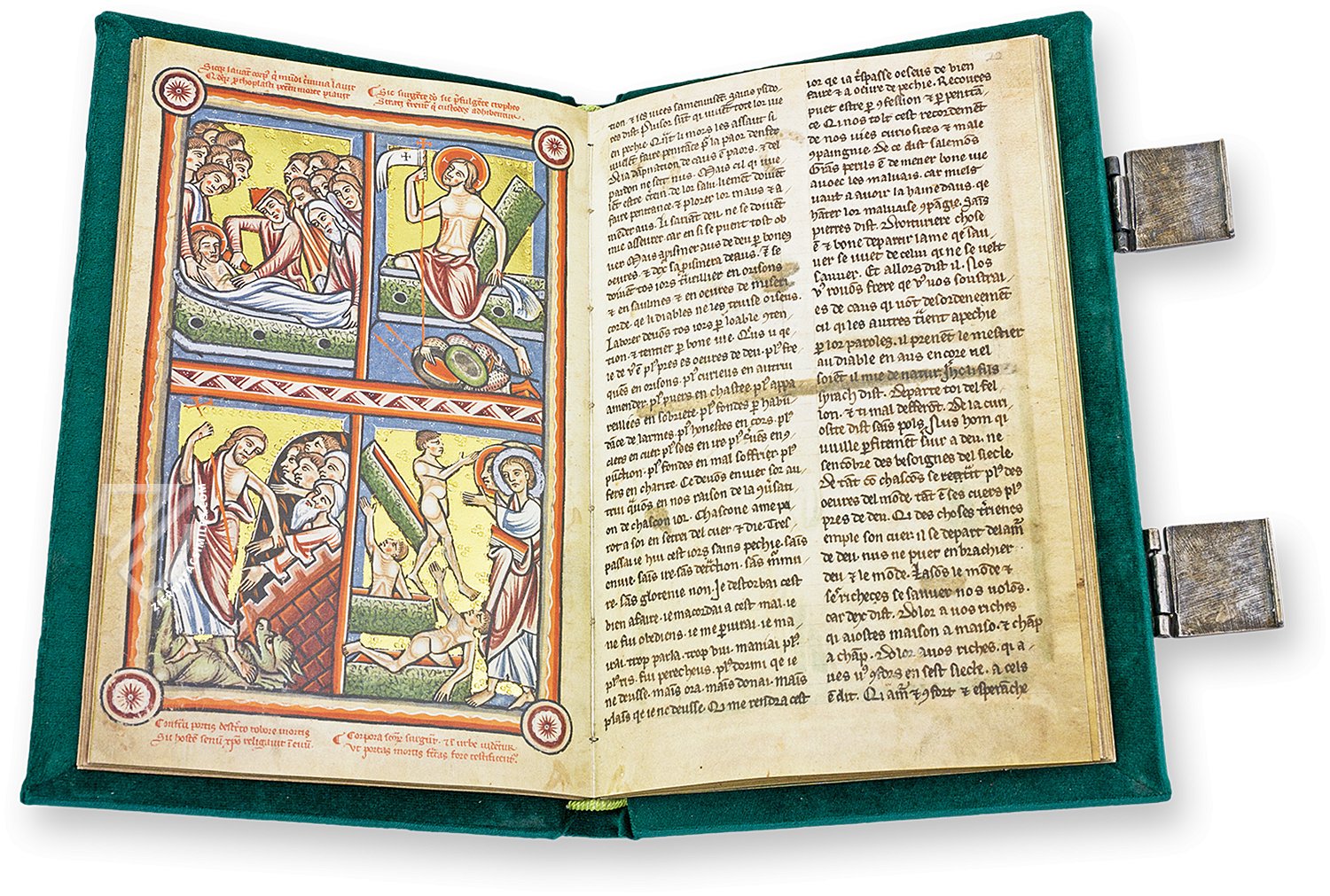

One iconographic variation actually presents hell as a mere sea of flames from which Christ rescues the souls of the righteous. In both the Gospel Harmony of Eusebius from Reichenau and the Echternach Pericopes of Henry III, several evil creatures are depicted shackled at the bottom of the picture, while Christ extends his redeeming hand to Adam.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

Salvation from Hellmouth

To the facsimile

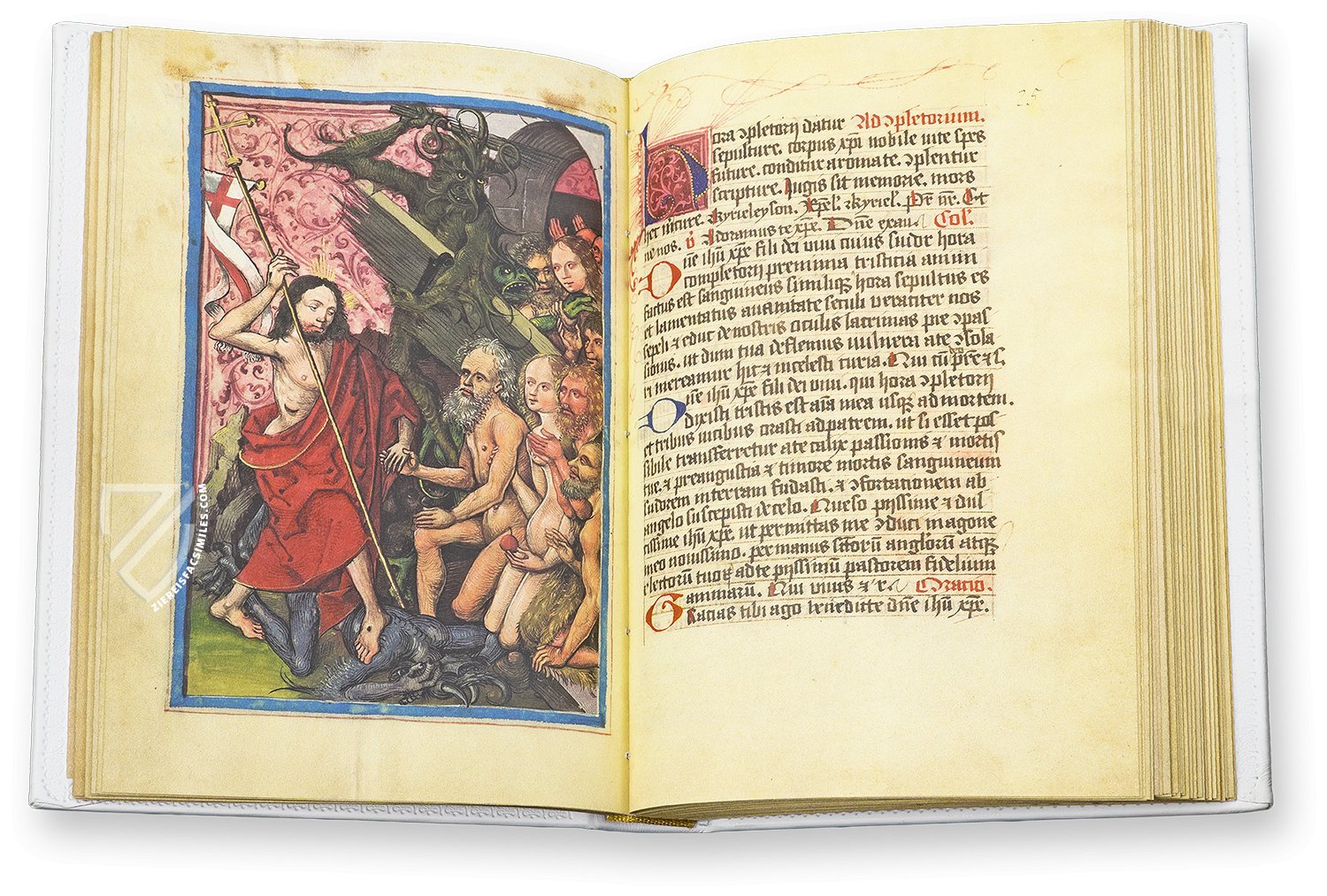

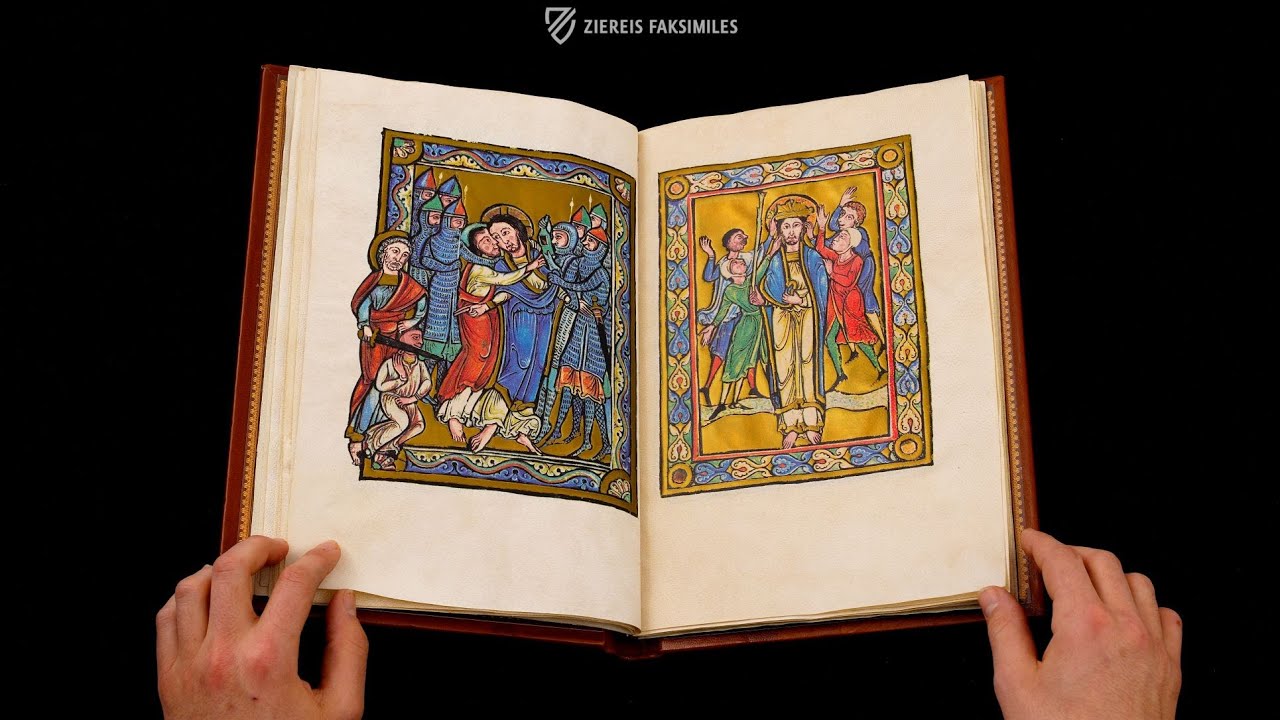

The High Middle Ages saw the emergence of a particularly fascinating and memorable variation of the iconography of Christ's Descent into Hell, which remained extremely popular until the 16th century: the entrance to the underworld appears here as a wide open zoomorphic snout with razor-sharp, long teeth, presumably reminiscent of a lion's mouth. The redeemed saints usually march out of the Hellmouth or are pulled out of it by Christ. The depiction is usually accompanied by infernal creatures and the vanquished Satan himself.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

In addition, the function of the beast's mouth as the gateway to hell is sometimes emphasized by allusions of architecture, for example in the Picture Bible of Saint Louis and the Très Belles Heures de Notre-Dame. In other images, such as the full-page miniaturess in the Liber Precum and the St. Alban’s Psalter, the broken doors lie before the Hellmouth and at the feet of Christ as a symbol of his powerful victory over Satan and Hades. This is further emphasized by the fact that Satan's contorted and bent body is pressed down by one of the doors.

Then the King of Glory seized the chief satrap Satan by the head and handed him over to the angels with the words: "Bind his hands and feet, neck and mouth with iron chains! (EvNic 6,2)

To the facsimile

The miniature in the Golden Bible - Biblia Pauperum is also a wonderful example of the typological, i.e. one that legitimizes the New Testament through the Old Testament, interpretation of Christ's Descent into Hell. The redemption from the Hellmouth is limited to a minimum of figures so as not to make the scene in this Paupers' Bible unnecessarily complex. The picture is accompanied by two Old Testament scenes that were understood as prefigurations of the event: David's victory over Goliath on the left and Samson's battle with the lion on the right. These were typical for the typology of the Harrowing of Hell in late medieval Paupers' Bibles. In other contexts, however, Christ's Descent into the Underworld was also juxtaposed with a variety of other Old Testament scenes.

Experience more

The Entrance to Hell in Ruins

To the facsimile

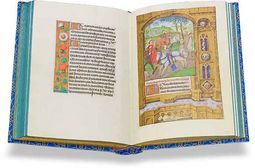

Around the same time as the Hellmouth variant, the tradition of depicting the gates of hell as fortresses was also established in Western Europe. Artists invented dramatic scenes in which Christ frees the righteous from castle-like structures that either appear to be collapsing or whose doors have been lifted off their hinges and shattered.

In late medieval depictions such as Simon Bening's Stein Quadriptych or the miniature in the Herrenalb Prayer Book Satan or Hades cling to the remains of the infernal doors, making the evil creatures appear all the more helpless in the face of the radiant Christ.

The Pictorial Descent into the Ground

To the facsimile

However, the entrance to hell is often also located in the ground, which seems quite plausible given the idea of an underworld in contrast to heaven. For instance, the gates of hell could be an opening in the ground from which Christ has to pull Adam out, as in the historiated initial of the Fitzwilliam Book of Hours.

To the facsimile

To the facsimile

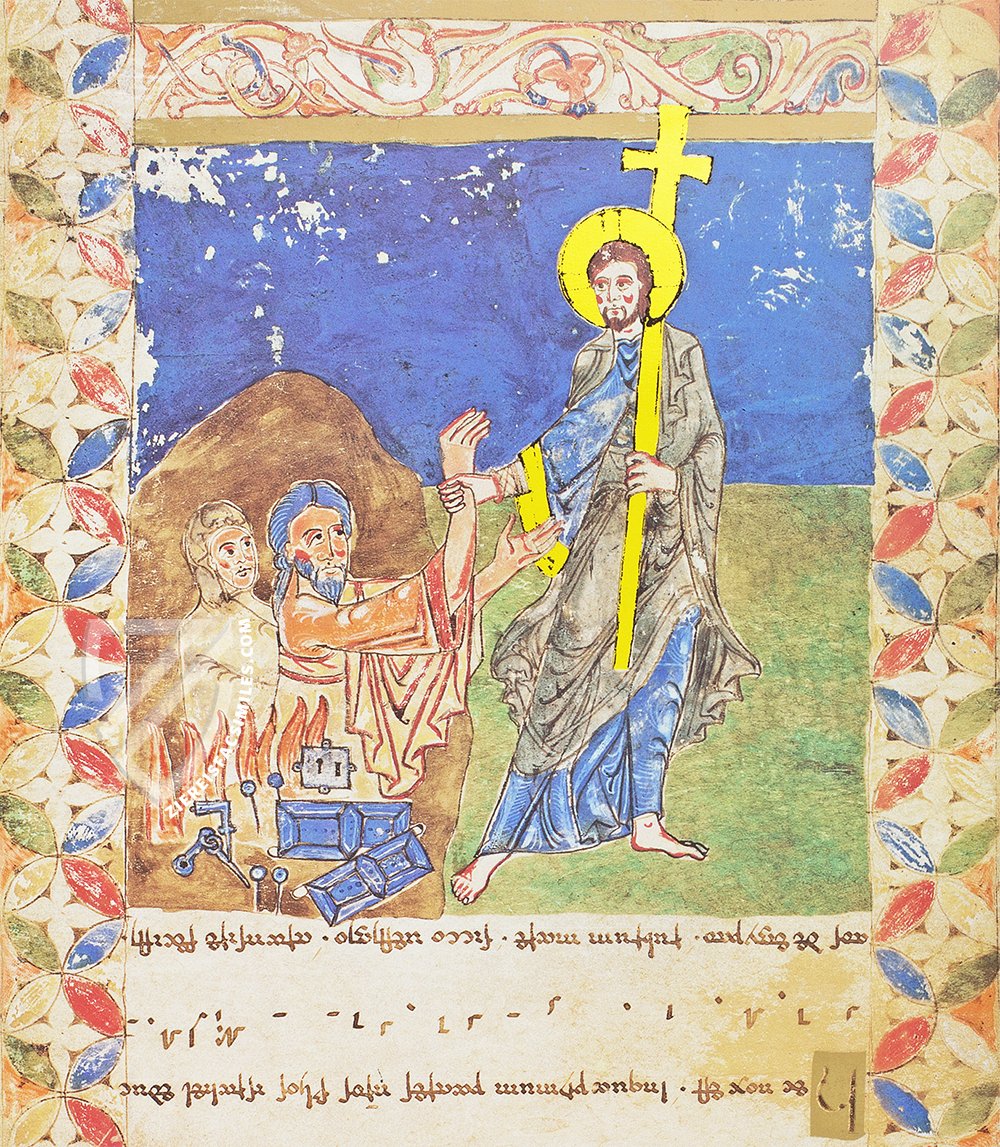

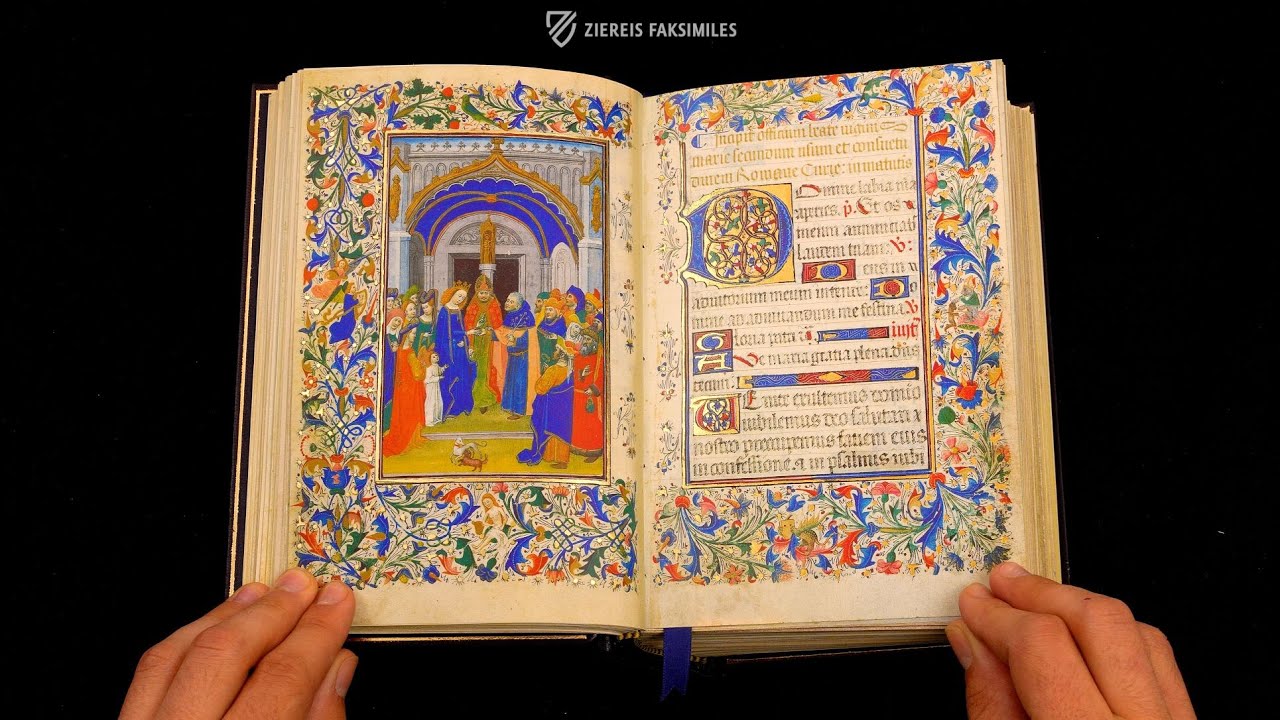

The Book of Hours of Isabel "The Catholic" shows another variation in two full-page miniatures: here the portal is located in a hill from which Adam, Eve and their holy companions can simply walk out after Christ has defeated and bound Satan and Hades. Dividing the apocryphal narrative into several images was a common strategy to present both Christ's battle with the guardians of hell and the salvation of the righteous in equal measure.

While Hades was thus speaking with Satan, the King of Glory stretched out his right hand, took hold of the forefather Adam and raised him up. (EvNic 8,1)

Experience more

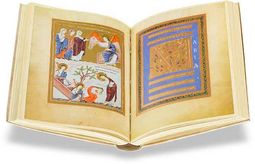

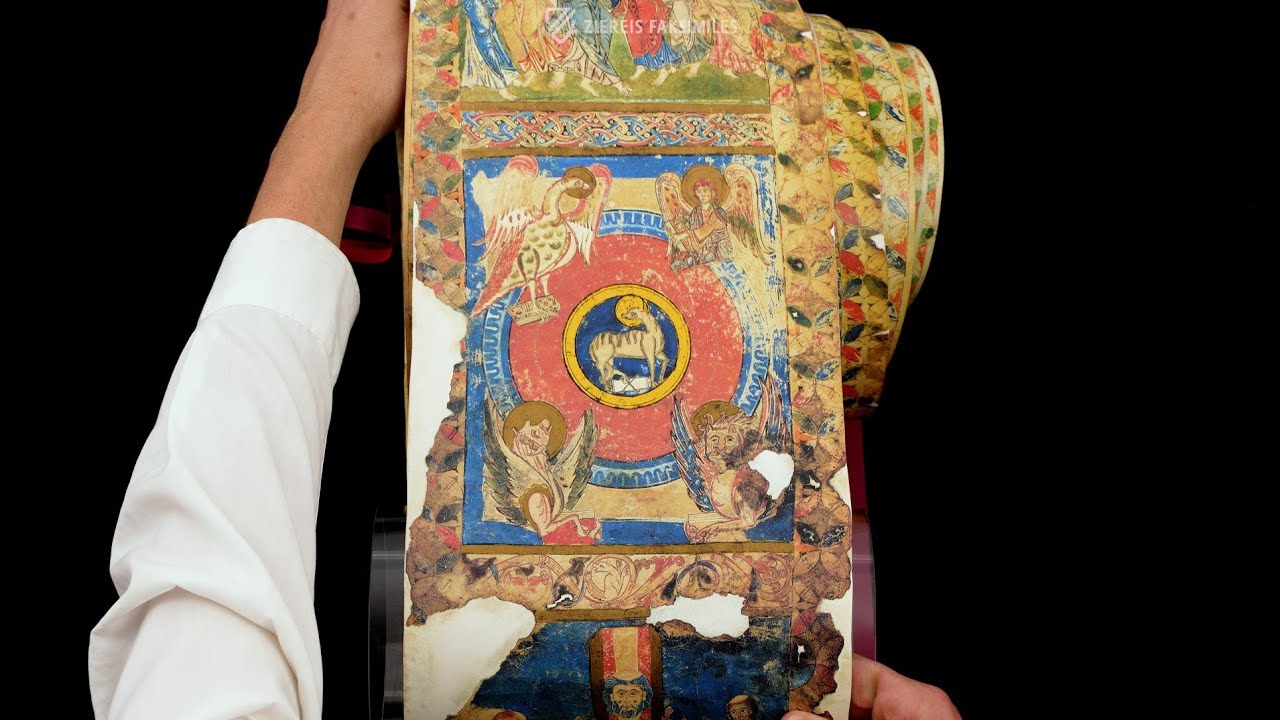

Unique Combinations of Pictorial Elements: The Harrowing of Hell in the Exultet Scrolls

To the facsimile

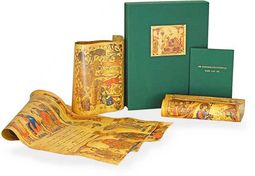

Finally, the depictions of Christ's Descent into Hell in the southern Italian exultet scrolls are particularly fascinating, combining Western and Eastern pictorial elements in a unique way. Exultet scrolls are used in the Latin liturgy during the Easter Vigil and contain the ceremonial doxology Exultet, which is usually illuminated with extraordinary splendor. As part of the Easter event, they usually illustrate Jesus' Descent into the Underworld.

While the flames in the miniatures presented here originate from the Western European pictorial tradition, the depiction of the defeated Hades on the ground in the Barberini Exultet Roll and the salvation of Adam and Eve from a minimalist sarcophagus in the Salerno Exultet Roll are clearly of Byzantine origin. In the Scroll Exultet and the Barberini Exultet Roll, the doors are truly shattered into all their components and thus emphasize the destructive power of Christ, which, however, is only directed against the powers of the netherworld.

Hence, the magnificent exultet scrolls bring together the various imaginative pictorial elements in the Easter Vigil and are a wonderful testimony to the great artistic range of the iconography of the Harrowing of Hell, which was further explored until the early modern period and inspired a large number of small and large artworks. At the same time, the pictorial subject visualizes an aspect of what is probably the most important aspect of the Christian faith: Christ's double triumph over death and the salvation of souls from eternal darkness.

Experience more